The Battle of Adrianople

by Igor Dzis

Roman triumphal parade

When through persistence and honor the republic achieved power, when great princes had been conquered by war, when barbaric tribes and peoples had been subjugated, when Carthage, Rome's rival for dominion, had been totally destroyed, and every sea and land was part of her domain, then fate turned against her.

Nearly eight centuries passed. From 390 BC to AD 378, Rome changed drastically. From a struggling little republic in the backwater of history it became an empire. The Romans conquered the Gauls in France and sealed off Britannia below Hadrian’s Wall. From the Atlantic to the Euphrates, the Rhine to the Sahara, the Western world yielded to Rome’s will. According to the late 4th-century writer Publius Flavius Vegetius Renatus, “The Romans owed their world conquest to nothing more than continuous military training, strict discipline in camp, and unceasing development of the art of war.” Yet in the 1st-century BC the Romans came up against a people, barbarians though they were, whom they could not defeat. According to the conqueror of the Gauls himself, Julius Caesar, these barbarians had been crossing the Rhine River out of Germania, their homeland beyond, and like him had driven the Gauls before them. In civilized fashion, Caesar met with envoys of these barbarians. They offered to become willing allies of Rome, if Caesar would allot them land in Gaul or cede to them that which they had already taken. If not, they warned, they could become implacable foes. Caesar declined their offer. Rome did not negotiate with barbarians. But Rome soon learned these Germanics – Vandals, Alemanni, Franks, Goths – were a breed apart from the Celts of Britannia and Gaul. They are thought to have numbered some fifty different tribes, and if they had ever united their empire would have covered a territory rivaling even the Roman. It was a united Germanic army under the leader Herrmann, called Arminius by the Romans, who dealt the legions a disastrous defeat in the Teutoburg Forest in the year 9, in which as many as 20,000 Romans were slaughtered. (That Arminius had lived among Romans and been given Roman military training was, like Brennus’s warning, another lesson the Romans forgot.) A string of similarly catastrophic defeats over the ensuing centuries dissuaded the Romans from expanding their empire into Germania. The Rhine, emptying into the North Sea, had its headwaters near those of the Danube, which emptied into the Black Sea, and together they formed a natural, though not insurmountable, border between civilization and barbarity. After their many setbacks, the Romans settled for Romanizing Germans on their side of the border. This policy of assimilatio – whether forced or not – greatly benefitted both Rome and barbarians. “This, more than anything else, is why Rome flourished,” declared Plutarch, “she always united and assimilated within herself those whom she conquered.” In the centuries after Brennus’s sack, the Republic extended citizenship to the surrounding peoples of Italy as they were conquered. Snooty patricians and equestrian classes may have looked down their noses at these new “Romans,” but no more than they did the city’s plebeians and slaves. Then, in the wildly expansive first centuries of empire, emperors realized that to control a huge domain was beyond even Rome’s manpower. They solved the problem by making nominal Romans of the barbarians in Gaul, Britannia, Hispania, and other conquered territories. Even Rome’s emperors came from wide-flung provinces: Spain, North Africa, Croatia, Serbia, Syria. And in AD 212 Emperor Caracalla went all the way, declaring every free man in the Empire a Roman. For a people, citizenship and assimilation meant dispersal throughout the Empire, losing their own culture, obeying Roman law and adopting Roman ways, when necessary enforced at the point of a sword. It required a conquered people to submit to Roman will. But as Caesar had found, some people refused to submit.

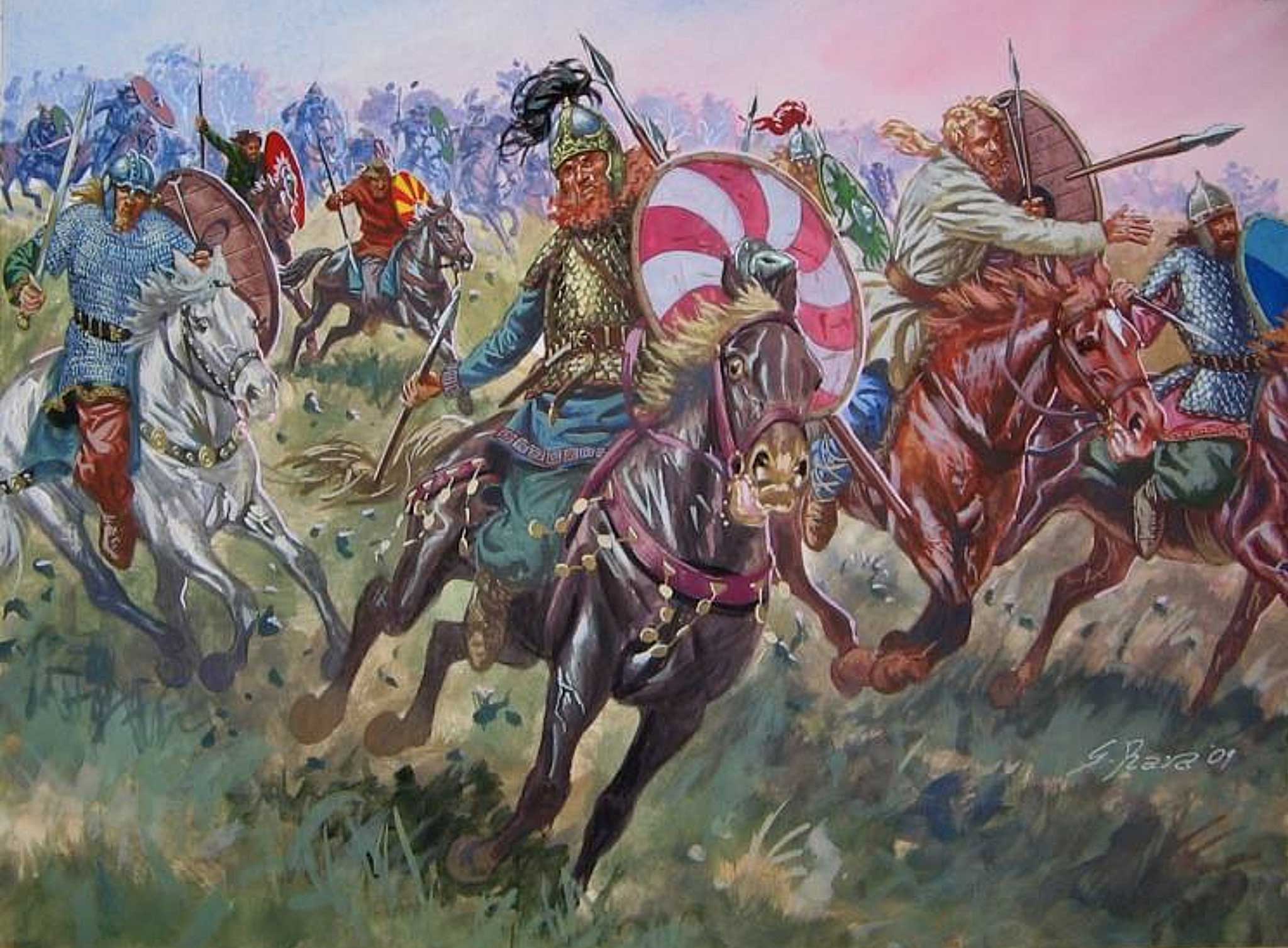

The Barbarians, by Angus McBride In AD 376 a Goth army crossed over the river Danube. Over the course of two years, they defeated a Roman army at the provincial capital of Marcianople, fought another to a draw and annihilated a third at the coastal city of Dibaltum, killing one Roman general and taking another prisoner. They ran rampant over Thrace, and wherever they went, woe and misery followed. “Without regard for age or sex they came, destroying everything in one vast massacre and burning,” wrote the contemporary historian Ammianus Marcellinus, “tearing babies from their mothers’ breasts and killing them, raping their mothers, butchering women’s husbands in front of them and making them widows, even as boys and young men were dragged over their parents’ dead bodies.” Greek-born Ammianus, himself a former imperial officer, was living in Rome at the time, but had served in the East and followed events there. “Numerous old men,” he wrote, “wailing that they had lived long enough as they had lost everything, and together with beautiful women, had their hands tied behind their backs, and were driven from their land, mourning the ashes of their homes.” On the evening of August 8, AD 378, the Roman Army of the East lay encamped beneath the walls of Andrianople, modern Edirne in European Turkey, about 130 miles northwest of Constantinople. Preparations were being made for battle against the Goths when one of their priests arrived from their wagon fort, ten miles or so distant. He bore messages of import from their king Fritigern for the Eastern Roman emperor, Valens.

Imperator Caesar Dominus Noster Flavius Valens, Augustus Flavius Julius Valens – Imperator Caesar Dominus Noster Flavius Valens, Augustus – was fifty years old. “He was indolent and slow, of a swarthy complexion,” remembered Ammianus, “with a cast [strabismus] in one eye, a flaw, however, which was not noticeable from a distance; his limbs were well formed, he was neither tall nor short, knock-kneed and a bit pot-bellied.” Over the fourteen years of his reign Valens had become all too familiar with these Goths. For a century and a half, they had alternated between begging the Empire for sustenance and invading to take it. Barely a year and a half into Valens’s rule, in 368, he had run them back over the Danube and returned to Constantinople thinking he was done with them. That, however, was before the coming of the Huns.

Hun warriors. Colored engraving from 1890, artist unknown. The Romans had as yet only rumors of this horse-borne scourge of the far eastern steppes, but the Goths had bitter firsthand experience. Caught between hammer and anvil, barbarians felt the Romans were the lesser of evils. As their priest reported, their king only sought sanctuary for his people in Thrace, imperial territory. If Valens would agree to that, Fritigern would call off the war. Land for peace. This was the same bargain Germanic peoples had sought from Caesar over four centuries past, and they were still seeking it. It must have annoyed Valens no end that he had already agreed to it, two years earlier, while away in Anatolia battling the Persian Empire. The influx of tax revenue and fresh recruits would have been welcome in his campaign against the Persians, and as a people the Goths would have served as a buffer against these Huns, whoever they were, if they became more than a threat lurking beyond the river. His administrators and officers on the frontier allowed the Goths over the Danube, but penned them on the Roman bank. Rations consisted of spoiled meat and moldy bread, the price of which soon reached untenable levels. The Goths traded away their slaves for food, and when the slaves were gone, they sold their children, including those of noble families. “The parents agreed even to this, in order to secure their children’s safety,” wrote the 6th-century Byzantine bureaucrat and historian Jordanes, thought to be of Goth blood himself, “reasoning that it was better to lose freedom than life; and certainly better to be fed as a slave, than starve in freedom.”

The Goths cross the Danube by Angus McBride This, however, may have been the Romans’ goal all along. Zosimus, the Byzantine court treasurer who would make his name instead as a historian, and who never spared the ancient Romans of any guilt, interpreted it less as slavery, or even as hostage-taking, than of compelling the Goths to hand over their future generation of leaders for assimilation. Valens had ordered them scattered into nearby cities to be raised as Romans. “The sons of the Goths had been judiciously distributed through the cities of the East,” wrote Gibbon, “and the arts of education were employed to polish, and subdue, the native fierceness of their temper.” Assimilation would have certainly benefitted the Goths as well as it had the Gauls, Britons, Franks, and all the other barbarian peoples before them. To be accepted as Roman citizens was all they wanted. To serve as mercenaries in Rome’s legions against the hated Huns would not have been too costly a price to pay. Alas, citizenship was not offered to them. And conditions along the Danube did not improve. The local Romans were making too much money from sales of cut-rate food and barbarian slaves. To the Goths it seemed that the Romans treated them little better than had the Huns. Accordingly, Fritigern simply led them off the reservation, into open Thrace.

Goth migration, by Howard Gerrard “That day was the end of the poverty of the Goths and the safety of the Romans,” concluded Jordanes, “for the Goths, no longer outsiders and refugees, but united as overlords, now ruled the locals and all the northern territory up to the Danube.” The subsequent victories had equipped the Goth warriors with captured Roman arms and armor, and swelled their numbers, including even Adrianople’s garrison of Goth mercenaries, who – beset by a hostile populace – deserted to join their barbarian brothers. So recently refugees in a foreign land, the Goths had become a mobile nation of perhaps a hundred thousand, moving over Thrace in a wagon train miles long. Even renegade Alans and Huns flocked to Fritigern, for barbarians rarely owed allegiance to any lord, but followed whoever might profit them most through victory. Fritigern himself was barely in control of them, as his priestly messenger revealed to Valens. “He had no other way to cool the anger of his countrymen,” according to Ammianus, “or to encourage them to accept Roman peace terms, unless when the time came he could show them an army close by and ready to fight, and by striking fear into them in the emperor’s name, allay their stubborn love of fighting.” The Goths had crossed the border seeking refuge, not war. They felt the recent battles had been forced upon them, and their victories had led only to more battles. As the Empire had proven again and again, it could always raise fresh armies, not least from among other barbarians. On the other hand, a defeat would cost the Goths everything. So, parade your army, Valens, but expect the Goths to flee at your approach, despite the fact that they had not dodged, nor lost, a fight against Rome so far. To the Romans, it had to be either some kind of trick or a colossal bluff. What civilized man could know the mind of a barbarian?

Late Roman imperial guardsman There’s no way to prove it, but a civilized barbarian was very likely attending that audience with the Goth priest in the imperial tent. In 378 Flavius Stilicho was in his late teens or a little older, but already a member of the protectores domestici, the imperial bodyguard, which also served as a cadet corps to train future commanders. As such, he would have witnessed his emperor’s dealings with the Goths and, if we flatter him a bit, may even have been consulted for his opinion, since he was half-barbarian by birth. Stilicho’s heritage comes down to us from only a few sources. In later years his veritable press secretary, the Egyptian court poet Claudian, never failed to extol his patron’s virtues, yet had little to say about his parentage. “I will not tell of your father’s warlike deeds,” he wrote to Stilicho. “Had he never done anything important, had he never led those red-haired companies in battle out of loyalty to Valens, simply being the father of Stilicho would have spread his fame far and wide.” In that period the “red-haired companies” in question, rutilantes crinibus alas in the original Latin, were mounted auxiliaries, barbarian cavalry. For all their innovations in infantry tactics and equipment, the Romans never developed much in the way of their own cavalry. They got their alae from the “allies” who supplied the old Republic with most of its horsemen, and the Empire by tradition still employed mercenaries in that role. In giving a job description for Stilicho’s father, Claudian renders it all but certain that he too was in the Roman camp at Adrianople. Stilicho’s contemporaries certainly considered him a half-breed. Jerome of Stridon, in a letter written a year after Stilicho’s death, called him semibarbarus, a half-barbarian. Whether he meant semi-barbaric by blood or by deed, Jerome had a low opinion of both. And fellow Roman priest, historian, and theologian Paulus Orosius would later claim outright that Stilicho “was born of the Vandals, that cowardly, avaricious, faithless, sly race.” Orosius was from Galicia, modern Portugal, where he wrote his Historiae Adversus Paganos, History Against the Pagans, some ten years after Stilicho’s death, when the Vandals were battling the Goths for control of Hispania and it was politically fashionable to blame Stilicho for the acts of both. In 378, though, the Vandals had so far been to the Goths what the Goths were to the Huns: victims. As the Huns had pushed the Goths into confrontation with the Empire, so the Goths had done to the Vandals, some half-century earlier. Some of the tribe had retreated west, into Germania, and others south, into Dacia, where Emperor Constantine, striking the eternal bargain with Germanics, assimilated them, granting them land and citizenship. Jordanes wrote of them, “Here they made their home for about sixty years and obeyed the emperors’ commands as subjects.” Stilicho’s father was probably born in this era, as a Roman citizen, and evidently rose through the ranks of the cavalry auxiliaries. All this vague ambiguity has led some historians to posit that Stilicho was in fact a full-blooded Roman who was simply derided for perceived barbarian sympathies, but that view is not widely held. The greatest evidence of Stilicho’s barbarian blood is simply his surname. Stilicho is not Latin, not Roman. It comes down from the proto-Germanic stillijaz, meaning still or quiet. No self-respecting 4th-century Roman would take such a barbarian name without good reason. As Romans typically named eldest sons after their fathers, we might also assume Stilicho’s father’s first name was Flavius, but then a full-blooded Vandal would perhaps not have adopted a Roman name except as an alias or nom de guerre. On the other hand, Flavius was a very popular and common Roman name, the equivalent of today’s English “John,” perfect to Romanize a little half-barbarian boy. That it originally meant golden or golden-brown may indicate that Stilicho had the fair hair of his Germanic ancestors. But what of his Roman ancestors? How Stilicho’s father, the barbarian cavalryman, met his Roman mother, and furthermore how that very unusual match turned to matrimony, will forever remain a romantic mystery, for she is otherwise a complete unknown. Judging by later female names in the family – Stilicho had a sister, of whom almost as little is known, including her name – historians guess his mother’s first name was Maria, and judging by her son’s high position at a young age, she may have been a daughter of a noble family, possibly even related to the imperial bloodline. Marriage between Romans and barbarians was frowned upon and actually made illegal in the early 370s, thereafter requiring conubium, imperial dispensation. By that time Stilicho was ten years old, and this is all speculation, of course, but sons of Roman servicemen were expected to serve in their turn, Stilicho was of military age, the military was beneath the walls of Adrianople with the emperor, and he was a member of the imperial bodyguard, training for the highest levels of command. Put all that together, and it’s conceivable, even probable, that he was there in the imperial tent as Valens and his generals decided how to deal with the Goths. He would not have been the only barbarian officer present. Bacurius Hiberus, “the Iberian,” was a prince of that country (modern Georgia), which had of late fallen under Persian sway, and he now served Valens as a tribune of cavalry. Zosimus called him “an expert in military matters, and not disposed to evil,” so circumspect about his religion that even his friends had no idea if he was Christian or pagan. Flavius Richomeres, a full-blooded Frank (another Germanic tribe, which had superseded the Gauls on the Roman side of the Rhine and, as allies of Rome, supplied its armies with mercenaries) was a comes domesticorum, count of domestic troops, a general in the Western army. He had been sent ahead as a liaison by Valens’s 20-year-old nephew, the Western Emperor, Flavius Gratianus. Richomeres had fought Fritigern and the Goths to a bloody draw, and from that experience advised Valens to await his nephew’s arrival before engaging them at Adrianople. And according to Ammianus, as Valens’s magister equitum, master of cavalry, Victor, “a man of measured and wary disposition, urged him to wait for his imperial ally, and in this was supported by a number of other officers, who thought the reinforcements by the Gallic [Western] army would likely cow the angry pride of the barbarians.” Though Valens’s barbarian commanders were united in their advice to wait, his Roman generals were eager to fight. Profuturus and Traianus, “ranking, ambitious officers, but with no great aptitude for war,” as Ammianus put it, had supported Richomeres in fighting the Goths to a draw, but won themselves no glory and wanted another crack at them. Traianus’ successor as magister peditum, master of infantry, was Sebastianus, a former governor of Egypt and a Western general who had bragged to Valens of his recent successes at hunting down random Goth foraging parties. These foragers were key to imperial strategy. Valens’s speculatores and exploratores, his spies and scouts, had reported the Goths numbered only about 10,000 warriors in camp – surprisingly few to protect such a large band of women and children – leading the Romans to think most of the enemy warriors were ranging over Thrace, scavenging provisions. Valens’s army was at least half again as large. (The exact head count isn’t known. Ammianus, whose chronicle of events is otherwise most complete, inexplicably neglects to tally manpower.) His nephew Gratian had been delayed putting down another German uprising along the Rhine, but was coming down the Danube to share the upcoming victory with his uncle.

Solidus of Gratian, c. 381. Inscription: D(ominus) n(oster) Gratianus p(ius) f(elix) aug(ustus). ("Our Lord Gratianus, the Devout, the Fortunate, the Majestic.”) This was not necessarily good news from Valens’s viewpoint. For a minimal contribution in manpower, Gratian would claim an equal share of the glory. There was already sedition in the streets of Constantinople due to Goths pillaging practically in the suburbs. Valens needed to appear as the defender of empire. If the scouts’ reports and Fritigern’s offer were to be believed, on the appearance of the imperial army the Goths would simply flee or submit. “The fatal intransigence of the emperor prevailed,” wrote Ammianus, “fortified by the flattery of some of the commanders, who advised him to hasten with all speed, so that Gratian might have no share in a victory which, as they fancied, was already almost gained.” When the priest and his retinue arrived back in the Gothic camp that night, word must have spread like wildfire that battle was certain on the morrow. The wagon train’s exact location is to this day uncertain, but most historians place it on a ridge line to one side or the other of the Tundzha River, north of Adrianople, where it had access to fresh water but was still defensible against attack. The Goths, who had been on the move for three days in search of sustenance, typically circled their wagons for the night, but Fritigern’s wagon train was a mobile city with a population on the order of 30,000 and probably 2,000 to 5,000 wagons. Nose to tail they would have made a circle a mile or more around, too thinly spread and vulnerable for easy defense, and they probably formed several tighter, concentric or spiraled circles. News of the impending fight would have run through this improvised fort almost as quickly as a bugle call. Men set aside their more mundane chores to sharpen notched sword blades and ponder whether donning their hard-won Roman helmets and armor would be wise on the morrow, considering the stifling August heat. Horsemen groomed their mounts and picked hooves clean of stones, for with Vandal auxiliaries in the imperial ranks (as the priest and his attendants would have observed) there was sure to be a cavalry fight. Women lingered over the evening meal, knowing it might be the last they shared with their men. Germanic warriors looked forward to battle as a chance to prove their mettle; being morose or fatalistic served no purpose. Therefore drink flowed, musicians played, there was dancing and singing in the firelight and children and dogs ran and chased among the wagons. It was an exciting time to be a boy among barbarians. In the year 378 Alaric of the Goths was just eight or nine years old, a good ten years or more younger than his future counterpart Stilicho and not yet old enough to be considered a man. That may be the reason he was still alive and free, being too young to have made much of a slave, as so many other Goth youths had been sold to their Roman masters. Alaric may have been high-born, but all that is known of his ancestry is that he was a son of the Balti, the “Bold” clan, whose name may reflect the Goths’ semi-mythic origins on the island of Gotland in the Baltic Sea. Alaric was said to have been born on an island himself: Peuce (anglicized as Pine) Island, in the very mouth of the Danube, today part of its silted-up delta but then a true island of some 540 square miles.

March of the Goths, by Arnold Böcklin At his age, having known little else, he might have taken Fritigern’s traveling nation to be the natural way of things, but it had not always been so for the Goths, arguably not since their Scandinavian days. The Romans saw the Goths as two peoples, the Tervingi, the “forest-dwellers,” and Greuthungi, the “steppe-dwellers.” In the 6th century the Roman senator Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus would make them better known as Visi (Western) Goths and Ostro (Eastern) Goths, when the former ruled Spain and the latter ruled Italy. In the 4th century, however, the Goths themselves made no such distinction. Families and clans mixed and mingled freely, coming together and parting as necessary, going their own way any time the pickings looked better elsewhere. Add in Hunnish mercenaries and their Alan compatriots and the mix became even more volatile. For any leader to have held them all together for such a length of time was something of an anomaly. In Fritigern’s tent that night there must have been some consternation that his cavalry commanders Alatheus, a king in his own right, and Saphrax, leader of the Alans, were somewhere further up the river valley, foraging for supplies. They may not have yet learned of the Roman approach, and if they had, it would not have been inconceivable for them to tarry a bit, leaving Fritigern and the Goths to face the enemy alone. Yet in name at least the Goths were united as one against Rome. Young Alaric, if he didn’t on that night before battle, would soon enough take a life-lesson from Fritigern’s example of leadership. For now, though, as a boy too young to join battle himself, it sufficed to admire warriors cheerfully facing what might be their last night on earth, perhaps to borrow one of their swords to swing and imagine the great deeds that might be done with it, and almost certainly take a moment to join them in prayer. To the majority of Goths, the Christian god and the Germanic god Odin were of small distinction. One had hung on a cross, and the other on a tree, both for the sake of their people. The difference was of little import. Barbarians worshiped whichever god their lord decreed.

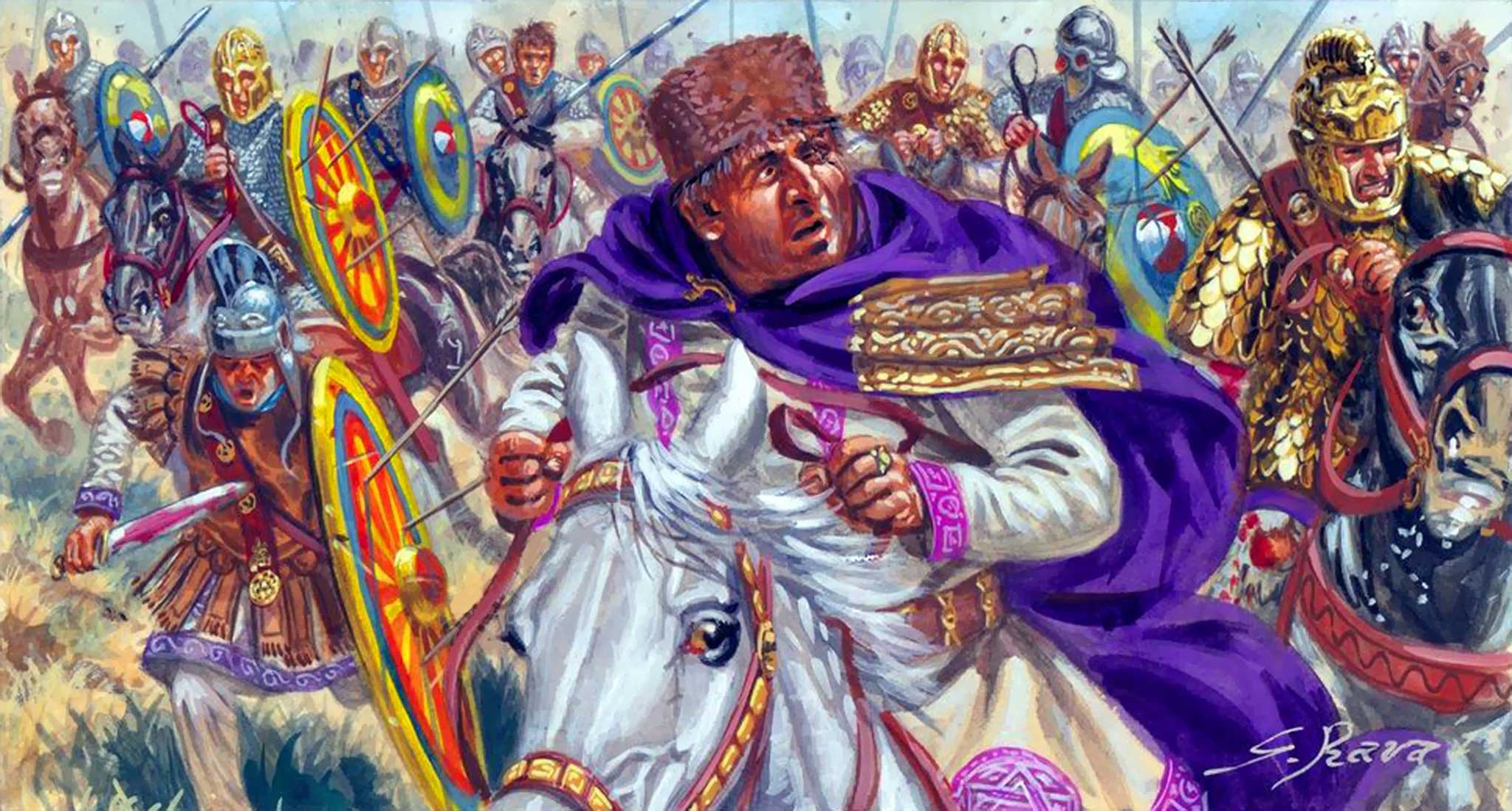

Marius’ Mules by by Radu Oltean At dawn the Roman Army of the East formed up for the march according to the age-old order set down centuries earlier by the Greek historian Polybius and the former Jewish rebel (later defector and scholar) Josephus. To ward off ambush, sagittarii and equites sagittarii, foot archers and light cavalry with bows or javelins, and the skirmishers, slingers, and crossbowmen of the light infantry ranged out ahead, with more cavalry fanning out to either side to screen the army’s flanks. Behind them came the vanguard, heavy infantry armored in lorica hamata, ring mail – a Celtic (barbarian) invention – and here in the East many in lorica squamata, scale mail. At the head of the main army rode the emperor, Valens, resplendent in his best armor. With him rode standard bearers to mark him for all to see, bodyguards to shield him, commanders and officers to carry out his will, and trumpeters and buglers to relay his commands. Then came the Army of the East. Two of the emperor’s personal armies, and probably three regional armies, those of the Orient (Syria), Thrace, and Illyricum (western Balkans). Heavy cavalry, mailed, bearing lances and broadswords with long reach. The awe-inspiring cataphracti, heavy shock cavalry, men and horses alike draped in mail from the head to the knees, faceless, terrifying. Five thousand legionaries, marching six abreast, bristling with spears, helmeted and armored, bearing heavy round shields (instead of the curved, rectangular scuta of bygone days). Six thousand auxiliaries – archers from Crete, Africa, and the Middle East, slingers from the Balearic Islands and Aegean, even a contingent of Arab cavalry and mercenaries. Border troops, scraped from the frontier forts, survivors of previous engagements with the Goths and probably not eager to face them again. Unusually, no baggage train followed this army. Wagons and carts, pack animals and slaves laboring along under heavy loads, ballistas and onagers (field crossbows and small catapults) for an army this size would probably have trailed behind for over two miles, but they make no appearance in accounts of the battle. Likewise, the usual parade of camp followers – women and children, sutlers, prostitutes, personal servants and slaves – that shadowed every army of the age appear to have stayed home this time. Valens seems to have anticipated a quick victory, or a show of strength followed by no battle at all, and a triumphant return to the city that evening. According to Ammianus, “the Roman banners were advanced with alacrity, the baggage having been left at the foot of the walls of Adrianople, with an adequate guard of legionaries. The emperor’s treasure and imperial regalia were inside the walls, with the prefect and the leading members of the council.” Where Stilicho was in all this went unrecorded. An as-yet-unknown youth, even among the protectores, he warranted no special mention in the annals. He may have been part of the “adequate guard of legionaries” who remained behind to guard the imperial freight, the treasury and officials. That he was a member of the imperial guard would seem to imply he rode out as part of the emperor’s retinue. That he survived the battle implies he did not. Over level ground Roman legions would normally have covered the distance to the Goth camp by mid-morning. The ground north of Adrianople, however, is not level, but rolls in successively higher foothills and deeper ravines, today’s Derventski Heights, severe enough to form a natural border between Bulgaria and European Turkey. The legions made only about a third of their usual speed, laboring up and down in the August heat. “Then,” records Ammianus, “having crossed the broken ground between the two armies, as the sweltering day was proceeding toward noon, finally, after marching eight miles, our men sighted the enemy’s wagons, which as the scouts said were all arranged in a circle.”

Goth chieftain, by Angus McBride What eight-year-old boy in the Goth camp would not have viewed the day’s events from under one of those wagons on the outer rim of the circle, peering through wheel spokes (or more likely between the wheels, if they were solid discs) to miss nothing? King versus emperor, surely a battle for the ages! Fritigern, at the head of his chieftains, leading the Gothic army out beyond the wagons onto the slope between them and the Romans, ready to face the enemy of his people in the open, his men waving their shields, spears, and swords in greeting the foe. “Following their tradition,” wrote Ammianus, “the barbarian army raised a ferocious, unnerving racket, while the Roman generals ordered their battle line.” The sight and sound of this barbarian horde, numbering many more than the 10,000 men his scouts had reported, must have given Valens pause, but he was committed now. In the hazy, dusty distance helmets and spearpoints glittered in the shimmering heat as the Romans arrayed their legions and cohorts in battle formation. “The right wing of the cavalry was in the vanguard,” Ammianus tells us, “most of the infantry was kept in reserve. But the cavalry’s left wing, of which a large number were still marching on the road, were coming as quickly as possible, though with much difficulty.” The perfect time to attack Roman legions was while they were still in the midst of their very civilized ordering, organizing, and positioning, yet Fritigern did not. He stalled, sending emissaries across the field under truce to talk. Valens, without the numerical advantage of which he’d been assured and now expecting the battle to be a much closer, riskier contest, nevertheless ran a bluff of his own, finding reason to turn the envoys away until his legions could form up. “The emperor, offended at their lack of rank,” reported Ammianus, “answered that if they wanted a lasting treaty, they must send him noblemen of adequate dignity.” The messengers returned to the Goths with the imperial demand. Fritigern gave it some thought, and sent them back with yet another offer: to negotiate himself, in person, in the Roman camp, if Valens would in turn send hostages of sufficient rank and value to guarantee his safety. Richomeres volunteered. Back and forth the envoys went, while the legionaries, warriors, and horsemen stood sweating it out under the summer sun. Fritigern was running out of time. By now it had to be common knowledge in the Goth camp that Alatheus, with the Goth cavalry, and Saphrax and his Alans were still nowhere to be found. If rumors of betrayal were not circulating among the women and children in the circled wagons, they might already be rife among the Roman high command. As the sun passed overhead and sank into the hot afternoon the imperial troops ran out of patience. Anyone watching from the Goth wagon fort might have noticed, even as the delegation with Richomeres was setting out to cross the field toward the barbarian lines, a ruckus over on the right. Some Roman auxiliary horsemen – probably Vandals, with Stilicho’s father perhaps among them, barbarians eager for glory against their ancestral foes – had taken it upon themselves to win the battle of Adrianople all on their own.

Roman cavalry, by Igor Dzis Ammianus claims these cavalrymen were under the command of Bacurius, the outcast Iberian prince, whom contemporary sources all regarded as skilled and courageous in battle. His attack, though impetuous and probably unplanned, was likely to succeed. The best way to defeat a wall of barbarian shields was not to tackle it head-on, but to turn its flank. Attacking one end of the line would turn the battlefield ninety degrees, leaving what had been the far end of the line suddenly in the distant rear. Most of the Goths had just been put out of the fight. And their wagon fort was wide open to attack. According to Ammianus, the imperial cavalry thundered right up to the enemy wagons. Barbarian women were no shrinking damsels when it came to a fight, nor were their children. Everyone in the Goth camp who could grab a weapon, would have – bows and arrows, javelins, swords; among barbarians, even eight-year-old boys could handle a knife – and all steeled themselves for a fight to the death. Yet this end-around by the Vandal cavalry was, as far as Goth warriors were concerned, nothing more than cowardice, and the greatest incitement they could have to fight to the death. Night had fallen before the first survivors found their way back to Adrianople, arriving before the torchlit gate in ones and twos. The battlefield had been so large and the action so disjointed that no one man could yet know the entirety of the shocking, disastrous turn of events. By piecing together the stories, however, the sentries, the garrison, the city officials, and later Ammianus, could relate the tale of Rome’s worst defeat in at least a hundred years.

Goth cavalry charge, by Giuseppe Rava Just as the imperial auxiliaries were about to assault the wagon train, they ran into a second troop of barbarian riders – Alatheus and Saphrax, with the Goth cavalry and Alans. “These, coming down out of the mountains like a thunderbolt,” wrote Ammianus, “dazed and slaughtered everyone who got in the way of their lightning charge.” The timing was so fortuitous that it seems obvious that Fritigern’s allies, as would Wellington at Waterloo, Meade at Gettysburg, and Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse at Little Bighorn, had taken advantage of the terrain to conceal themselves, awaiting the moment to strike. And now the moment was upon them. The Roman auxiliaries, having ridden so far forward, found themselves all alone, trapped between the oncoming horsemen, the wagon circle, and the main Goth battle line. Ammianus admits, “They were abandoned by the rest of the cavalry and, hard-pressed and outnumbered by the enemy, overwhelmed and crushed, like the ruin of a walled fortress.” A cloud of sun-dried dust, churned up by the milling horses, obscured the glitter of swords, the flicker of arrows, and men tumbling from the saddle. “And while weapons and missiles of all sorts were clashing in vicious battle, and Bellona [goddess of war], blowing her trumpet of woe, was raging more wildly than usual to inflict catastrophe on the Romans,” concluded Ammianus, “our men began to retreat.” Orosius, writing nearly four decades after the battle, was harsher in his judgment. “As soon as the Roman cavalry squadrons were thrown into disarray by the Goths’ sudden charge, they left the infantry companies totally exposed.” The auxiliaries – those who survived – wheeled their horses as best they could and made for the safety of the Roman lines. The Goth and Alan cavalry pursued, all the way around the right end of the barbarian shield wall and the Roman left as well, effectively turning the tables on the imperial line. Now it was the legionaries who were outflanked. Unlike the Romans, however, the barbarians made this no half-hearted attack. Richomeres’ gambit be damned, Fritigern saw his chance and took it. Roaring, the entire Goth line surged forward, an unruly mob, but with edged weapons. That concerted effort was their only attempt at tactics. The Roman legionaries, though – Gauls, Franks, Sarmatians, even Goth mercenaries – were hardly less Germanic than Fritigern’s Goths. They had been raised in a tradition of all-out barbarian warfare, but honed by Roman training and discipline to a fine edge. A Goth charge did not intimidate them. They stood firm and held their ground. “Then the two lines of battle smashed into each other, like the rams of ships,” recorded Ammianus, “and shoving with all their strength, were tossed back and forth like ocean waves.” The melee was a confused, pushing, shoving scrum full of deadly points and edges. Arrows, javelins, and lead-weighted darts, plumbatae, arched overhead to drop onto unsuspecting targets among the closed-packed throng, and to raise a shield against them left a man exposed to a killing blow. The legions had long since given up the gladius, the short stabbing sword of the Republican days, in favor of the longer barbarian-style broadsword, and the Goths were armed much the same, but in that tight-packed brawl there was hardly room to swing or thrust. According to Ammianus the combatants were “so crowded together that a soldier could scarcely draw his sword, or pull back his hand after reaching out.” Even so, the legionaries in their armor might have withstood the assault by half-dressed barbarians.  The battle of Adrianople It was that impulsive initial charge, and subsequent repulse, of the imperial auxiliary on the left that was Rome’s undoing. The Goth and Alan cavalry, having driven the imperial auxiliaries from the field, found themselves unopposed, with the enemy battle line stretching away before them and the Roman flank, already engaged with the Goth infantry to their front, laid utterly bare. The Romans who had sought to turn the battlefield ninety degrees suddenly found it turned back upon them. The barbarian cavalry swept in behind them.

Romano-Vandal infantry at Adrianople, by Angus McBride The Battle of Adrianople in AD 378 (there were at least seven others, in 324, 813, 1205, 1254, 1365, 1829, and 1913, leading to the city’s claim to be some of the most fought-over ground in history) has often been characterized as a victory of cavalry over infantry, a signal change in warfare marking the rise of the armored knight who would dominate the Middle Ages. But in truth most of the fighting took place on foot, with sword, spear, and shield, where men cursed and stabbed, hacked and clawed, no longer for the Empire nor for some imagined Gothic nation, but simply for their lives. Most of them, on the imperial side at least, did not succeed. Not even a Roman legionary could stand against barbarian warriors to his front while barbarian riders closed in from behind him. The Goths enveloped the imperial left flank, crushed it as in a vise, and began rolling up the enemy line. As a former officer, Ammianus well knew the horrors of ancient man-to-man combat: When the barbarians, pouring forward in immense numbers, overthrew horse and man alike, and in the press of battle no direction to retreat could be found anywhere, and the crushing crowd left no chance of escape, our soldiers too, showing extreme contempt of death, received fatal blows even as they struck down their foes, and on both sides the stroke of blades split helmet and breastplate. In vain. Courage and valor matter little when tactics have failed, and at Adrianople civilized warfare proved insufficient against sheer barbarity. In the end the Goths simply swarmed over the Romans. Ammianus, with access to survivor testimony, recorded, “Finally our ranks were broken by the oncoming mass of the barbarians, and since that was their last chance, they took to their heels and fled as best they could.”  Valens at Adrianople, by Giuseppe Rava Those, according to Orosius, were the lucky ones: “Then the infantry legions, surrounded on all sides by enemy cavalry, first overcome by showers of arrows and then crazed with terror, scattered and completely cut to pieces by the swords and spears of the pursuers, were slaughtered.” Curiously enough, most of Valens’s barbarian commanders escaped. Richomeres got away, as did Bacurius and Victor. But Traianus, Sebastianus, and no less than thirty-five Roman tribunes were left among the dead. Only the fall of darkness prevented total annihilation. Adrianople was the worst defeat for the Romans since their loss to the Sassanid Persians at Edessa, a little over a century earlier. Ammianus, claiming two-thirds of the imperial army died on the field, deemed it worse than that: Rome’s greatest defeat since the loss to the Carthaginian, Hannibal, at Cannae, 600 years in the past. As little mention there is of Stilicho’s father before the battle, there is none after. If he lived to see the defeat at Adrianople, he most certainly did not live through it. As for Stilicho himself, if he took part in the campaign, his survival is more proof that he never left the city, because the citizens of Adrianople shut the gates to the survivors. The city fathers anticipated a siege, in which case the fewer mouths they had to feed the better, and a bunch of worthless losers and cowards weren’t going to contribute much to the defense. And the one man who would certainly have been admitted into the city, Emperor Valens, never returned. There was no moon that night. The battlefield lay blanketed in darkness, footing on the slope of the ridge made tricky with congealing blood, spilled entrails, and the tangled limbs and bodies of men and horses. The families in the Goth circle welcomed the survivors back to their fires. “The soldier takes his wounds to mother and wife,” wrote Tacitus, “who do not hesitate to count or even question them, and who deliver both food and comfort to them.” All turned their backs on the dead and dying outside the wagon wall, for barbarian or not, those were Romans. The moans and cries of the suffering were drowned out with a victory celebration.

Death of Valens, by Vladimir Kapustin Before dawn the Goths were out looting the battlefield. For a barbarian boy it would have been a treasure trove more valuable than gold: helmets and shields, swords and spears and daggers. Smoke probably still rose from the farmhouse to the Roman rear where, a prisoner had told the Goths, the Emperor Valens had fled after being hit by an arrow. He was still being treated when Goth warriors, not knowing who was within, came to ravage the house. “While the pursuers were attempting to break down the bolted doors,” Ammianus reported, “they were showered with arrows from a balcony above, and fearing the delay would cost them the chance for pillage, they piled bundles of straw and firewood against the house, set them on fire and burned it down, men and all.” The prisoner, who had survived the blaze by jumping out a window into captivity, informed the Goths they had burned Valens inside (and, doubly lucky, the same prisoner later escaped to tell the tale for posterity). They were very sorry. Not for having killed an emperor, of course, but for having lost the glory of taking him alive. And when the battlefield was picked clean and there was no longer any such thing as an ill-equipped Goth, the warriors all regrouped and set out on the march for Adrianople. Looting a battlefield was one thing. Looting a city was another. The barbarians had no knowledge of sophisticated catapults and siege towers, and unlike Brennus’s Gauls before the walls of Rome, Fritigern’s Goths were not accommodated with city gates left wide agape. Imagine their surprise on finding the remaining third of the Roman army penned outside the walls, much as the Goths had been penned on the banks of the Danube. Truly there was no pity in the Empire, and in their dealings with it the barbarians had lost theirs as well. Ammianus is unclear on the details of the brief siege. There seems to have been a bit of a struggle, before some 300 of the Roman troops, mostly barbarians themselves, ventured out with a plea for mercy and an offer to switch sides. The Goths put them all to death in sight of the walls. As though the gods disapproved, a summer thunderstorm dampened the barbarians’ sense of urgency. They retreated back to their wagons and contented themselves with sending a priest to implore the city to surrender, and Roman deserters to trick their way inside and open the gates. These ruses failing – the deserters were beheaded – the barbarians tried an all-out assault on the bastions, which also failed. Unable to take a small city, Fritigern then convinced his people to follow him in taking a great city, no less than Constantinople, capital of the Eastern Empire. The results were predictable, though not for the reasons that might be expected. Stymied by its great wall (built by Emperor Constantine thirty to forty years earlier; the city, though already imposing, was not yet anywhere near the impregnable fortress it would become through the Middle Ages), and battling imperial troops outside the city, the barbarians were ultimately put off by a single man, an Arab mercenary. Naked, he slew one of the Goths, cut his throat and, in plain sight of all, sucked out his blood. It was enough to put off even Fritigern’s warriors. Even barbarians weren’t that uncivilized. So the Goths marched off, little Alaric among them, leaving Constantinople in peace. The lesson was clear to all. Barbarians could destroy entire armies in the field, even Roman armies. But great cities – the very highest achievement of civilization – were beyond their ability to conquer. But a more accurate interpretation of events was, the barbarians simply weren’t yet civilized enough to take down a civilization. REVIEWS:

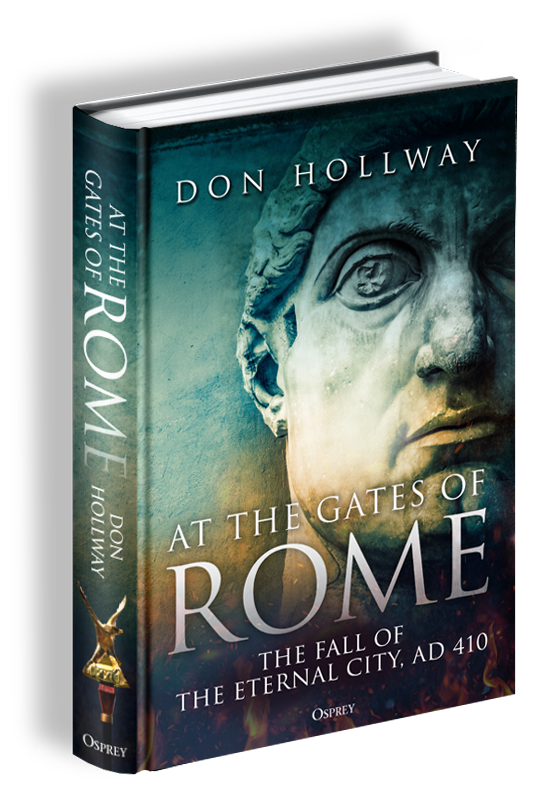

After reading this book, the fall of Rome feels less like revenge, even less like a tragedy, and more like a moment of justice. It is a multi-faceted story about empire, humanity’s basest instincts, and how the motives of the powerful often lead to the suffering of the weak. For those who love the subject of Ancient Rome, this book is a must-read. For everyone else, I would find it hard to not call this a must-read. It is a fascinating story written by a great storyteller.

In less assured hands, this could have been a turgid and thoroughly bewildering read. Thankfully, Don Hollway knows his subject inside out and neatly picks his way through the convoluted history of the late Roman Empire.... Hollway eloquently describes a treacherous, fragile world, in which the greatest empire the world has ever seen slowly collapsed under its own weight.... Overall, I very much enjoyed this excellent study of the fall of a centuries-old empire, scholarly but never dull. Thoroughly recommended. To say I thoroughly enjoyed reading this book would be an understatement. Well written, witty, and very informative, it reads like a novel, yet is non-fiction. It strikes a good balance between too academic and flippant, covering off all the relevant history at a good pace, not getting bogged down in excessive detail; I’d read several chapters in a sitting, with a single malt or coffee as company. Very recommended to persons interested in ancient Rome, or those who would like a good read. A gifted storyteller, Hollway wraps his narrative around the lives of two men prominent within the maelstrom of intrigue and war: Flavius Stilicho, the supreme military commander of Rome, and Alaric, king of the Goths.... Whether describing battles or political plots, Hollway has a knack for breathing life into history. At the Gates of Rome is a solid work of scholarship as well as a good read. Fans of Hollway’s short work already know his outstanding narrative style is matched by his impressive range. Coming on the heels of his medieval masterpiece The Last Viking, At the Gates of Rome brings Hollway’s marriage of thrilling storytelling and historical rigor to Late Antiquity. In this illuminating page-turner, Hollway walks us through the fate of one of the most significant civilizations in human history. There are works of history we return to as reference, and those we return to as inspiration. In At the Gates of Rome, Hollway has given us both. Don Hollway’s At the Gates of Rome is a masterful blending of solid scholarship and excellent storytelling that brings the Eternal City’s turbulent early history to vibrant life. Patricians and barbarians, slaves and saints, victors and vanquished leap from the pages fully formed, making the book an enthralling read from the first page to the last. The author uses the descriptions of ancient writers and more recent histories to create this account of the Western Empire’s final years. A wide range of figures are included, giving depth and detail to the narrative and revealing the vast scale of the Roman Empire and its adversaries. With so much of the writing on the Late Roman Empire dated, it is refreshing to read a work that offers a fresh interpretation of the events. ORDER TODAY:

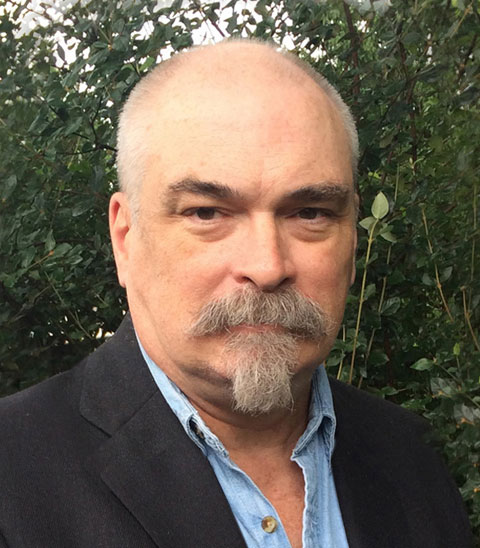

• AMAZON • PUBLICITY CONTACTS: REPRESENTATION Scott Mendel, Managing Partner About the author

Author/historian/illustrator Don Hollway has been published in Aviation History, Excellence, History Magazine, Military Heritage, Military History, Civil War Quarterly, Muzzleloader, Porsche Panorama, Renaissance Magazine, Scientific American, Vietnam, Wild West, and World War II magazines. His first book, The Last Viking, a gripping history of King Harald Hardrada, was acclaimed by The Times of London and Michael Dirda, Pulitzer Prize-winning critic for the Washington Post. Hollway is also a classical rapier fencer and historical re-enactor. His work is also available across the internet, a number of his pages scoring extremely high in global search rankings.

More from Don Hollway:Comments loading....

© 2022 Donald A. Hollway |