The Sack of Rome

by Andre Durenceau

National Geographic

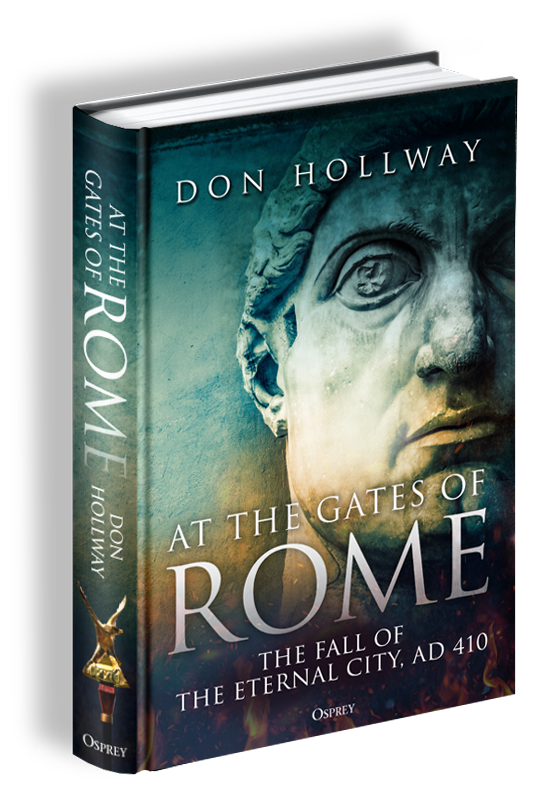

AT THE GATES OF ROME:

INTRODUCTION

MARCH, 1781

Over 1,300 years after the fall of the Western Roman Empire, and almost three centuries after that of the Eastern, Rome’s former dominions had yet to improve on its imperial system of governance. Most of Europe was ruled by a handful of absolute monarchs, all shoving and elbowing each other for territory, power, and prestige. They may have fancied themselves as enlightened despots, looking out for the best interests of their subjects, but they were despots all the same.

In Scandinavia, Christian VII of Denmark-Norway, only half as insane and lecherous as the worst Roman emperors, ruled a North Atlantic empire stretching across the Faroe Islands and Iceland to Greenland, when he wasn’t frequenting brothels or servicing his mistresses. In Vienna, Emperor Joseph II’s efforts to preserve the Holy Roman Empire, which encompassed little of ancient Rome and much of modern Germany, came at the expense of the Germans, who had contributed greatly to the Roman Empire’s downfall. Joseph’s nemesis, Prussian King Frederick II, the Great, was laying the groundwork for the Germans to dominate the Roman Empire once again, employing his military genius, his father’s brutal military discipline, and a long line of male favorites. In St. Petersburg, Empress Catherine the Great sought to expand Russia at the expense of the Poles and the Turks, while her own parade of lovers gave rise to rumors of extreme debauchery. King Louis XVI’s France was going bankrupt, financing and fomenting military revolution abroad. And Charles III of Spain, whose empire still controlled half the New World from Alaska to the tip of South America, was backing that same revolution, intent on retrieving his recent losses to Great Britain, including Florida and Gibraltar. The object of all that revolution, Britain’s George III – also subject to bouts of insanity – was the least absolute ruler of them all. “I wish nothing but good,” he insisted, “therefore, everyone who does not agree with me is a traitor and a scoundrel.” Only his parliament and his subjects’ treatment of his predecessors (variously overthrown, exiled, and beheaded) held his tyrannical inclinations in check. London was abuzz that spring. Britain had set itself again at war, not only with its thirteen American colonies but with France, Spain, the Dutch Republic, and their colonies too – a veritable world conflict, in which Britain had no allies. News from across the Atlantic, always weeks out of date, was not good. The French had landed troops and were fighting alongside the rebels. The previous November a naval expedition against Spanish Nicaragua under dashing young Captain Horatio Nelson had withdrawn with 2,500 casualties to yellow fever and nothing to show for it, the costliest British loss of the war. In January the rebels had defeated a British army at Cowpens in South Carolina. And that very month, as yet unknown in the mother country, the rebel commander George Washington had set his French protégé Gilbert du Motier, the Marquis de Lafayette, in motion toward cornering British general Charles Cornwallis on the Yorktown peninsula, the campaign that would ultimately end the war. Yet in their pubs and marketplaces the British middle class were largely ambivalent, even sympathetic toward the colonists, who sought only the same freedoms their domestic cousins already enjoyed. The loss of revenue and business partners in the Americas posed a greater threat to the British than some insult to King George’s pride. Could their empire, itself only some 200 years old, survive the loss of two and a half million of its subjects, and all their trade with them?

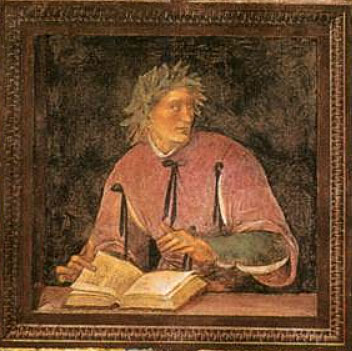

Edward Gibbon, by Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792) At 7 Bentinck Street, in the Marylebone section of London, a 43-year-old Member of Parliament (M.P.) and part-time historian named Edward Gibbon was going some way toward answering that question. On the first of that very month, he had published the second and third volumes of The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. It was far from complete (the sixth and last volume would not come out until 1788), but in Volume III he had covered the fall of Rome itself in ᴀᴅ 410. Gibbon’s British readers – and every British and American reader since – naturally perused his accounts of that earlier empire for any indicators of the fate of their own. Even Americans of the day appreciated the similarities. “Dr. [Benjamin] Franklin,” Gibbon’s fellow M.P. Horace Walpole wrote that April, possibly in jest, “…said he would furnish Mr. Gibbon with materials for writing The History of the Decline of the British Empire.” The idea for his masterpiece had come to Gibbon sixteen and a half years earlier, as a young man coming off a flirtation with religion, a broken romance, an uneventful stint in the military, and an escape from an overbearing father. As did many young upper-class Englishmen of the day, he had departed on a Grand Tour of the Continent, to become acquainted with foreign customs, art and culture, and along the way find meaning and perhaps himself. It was in Rome, an obligatory stop on such a tour, that Gibbon found his answer. In the 18th century the city was becoming a mecca of art and culture to rival that of Florence and Venice a few centuries earlier, perhaps unseen since the days of the Empire itself. This renaissance had fired the excitement of Enlightenment artists and thinkers, in awe of a civilization which, despite the passage of thirteen centuries, in many ways still overshadowed their own. Steam power, machine tools, and mechanized factories were not yet widely adopted. Despite gunpowder, the printing press, and Christianity, Western man did not live a life much removed from that of his Roman forebears. In Gibbon’s day, men still rode horses and carts and killed one another with edged and pointed steel. What could the past offer that still bore a lesson for the present? Of the once-glorious Forum of Rome – the Curia Julia where the senate met for over 650 years, the Temple of Saturn, the Arch of Septimius Severus, the Temples of Vesta and of Castor and Pollux and more – nothing remained but crumbling ruins, overgrown with weeds.

Rome, much as Gibbon would have seen it.

To Gibbon, however, that was the point. “I can neither forget nor express the strong emotions which agitated my mind as I first approached and entered the eternal City,” he wrote. “After a sleepless night, I trod, with a lofty step the ruins of the Forum; each memorable spot where Romulus stood, or Tully spoke, or Caesar fell, was at once present to my eye; and several days of intoxication were lost or enjoyed before I could descend to a cool and minute investigation.” It would be a turning point in the history of Rome. Not in the same manner as, say, Caesar crossing the Rubicon, Christ being crucified, or Diocletian dividing the empire in two, but a literal change in the history of the “Eternal City,” the manner in which it was written, and how future generations viewed it. “It was at Rome, on the fifteenth of October 1764,” recalled Gibbon, “as I sat musing amidst the ruins of the Capitol, while the barefooted fryars [sic] were singing Vespers in the temple of Jupiter, that the idea of writing the decline and fall of the City first started to my mind.” In that year Britain was fresh off victory in the Seven Years War (in the American colonies called the French and Indian War), taking as its prize most of France’s North American territory. The British Empire had never seemed further from a fall, and Gibbon put the book, as perhaps irrelevant, in the back of his mind. Not until 1769, by which point Gibbon had already distinguished himself as a man of letters (though, in parliament, by never making a single speech), and the Americans were making noises about rebellion, did he first put pen to paper to attempt the task at which many earlier historians had failed. The work was made all the more daunting because Gibbon, unlike his predecessors, disdained secondary sources. “I have always endeavoured,” he would write, “to draw from the fountain-head…my curiosity, as well as a sense of duty, has always urged me to study the originals.”

Edward Gibbon home, London, In what he called his “little palace” on Bentinck Street, Gibbon had amassed one of the great personal libraries of the age. (Late in life he undertook to catalog his books, using the backs of playing cards as his index. He left the task unfinished at his death, when the total was nearing 2,700.) He could take down and open any of these volumes and in his mind’s eye see the pillars and temples of Rome rise from the pages and hear the ancients speak to him. In June of 1781 he wrote to Lady Abigail Sheffield, wife of his good friend, constant patron and frequent country-manor host John Baker Holroyd, 1st Earl of Sheffield: “I am surrounded with a thousand acquaintances of all ages and characters, who are ready to answer a thousand questions which I am impatient to ask.” .jpg)

St. Ambrose There was Aurelius Ambrosius, governor of Liguria and Emilia before becoming bishop of Milan and ultimately St. Ambrose, simultaneously one of Gibbon’s least favorite sources and one of his most-quoted. Zosimus Historicus, Zosimus the Historian, whom

They were but a few among many. (For a full accounting of sources, see the listing at the back of this volume.) By combining and comparing their accounts, Gibbon was able to do what no historian had done before. The scope of his History is truly monumental, requiring some 1.6 million words, over 700,000 in the first three volumes alone. (For comparison, that’s over twelve times the length of this little 130,000-word pamphlet.) It spans 1,500 years, from the death of Emperor Nerva and the succession of Emperor Trajan in ᴀᴅ 98 to 1590, when Rome was about to embark on a new Golden Age of baroque art and culture, the age of Caravaggio and Bernini. Gibbon’s Empire included both West and East, the Holy, and the Catholic. Our focus, however, will be much narrower: the few decades leading up to the critical year of ᴀᴅ 410, in the West, the Rome of his initial inspiration. That Rome is not as epic sword-and-sandal films portray it, with hawk-nosed legionaries, sweaty gladiators, haughty patricians, and high-born ladies in clean, neatly draped stolas, a Rome still bending the world to its imperial will. Those days were gone. Our Rome was spiraling down into chaos. Gibbon took the reign of the emperor Commodus, a dissolute would-be gladiator who ruled thirty years from ᴀᴅ 161 until his assassination in 192, as the beginning of the end. Over the ensuing 180 years the Empire nearly self-destructed in the “Crisis of the Third Century,” decades of civil strife, economic upheavals, plague, invasions, and warfare. What came out at the far end in the mid-330s was an empire divided in two, East and West, each theoretically ruled by a senior emperor, the Augustus, and a junior emperor, the Caesar. The shining new capital of the East was Constantinople, where Europe and Asia met. In the West, it had long been Mediolanum, on the broad, flat valley of the River Po, closer to the geographic center of the Western Empire. In Rome, the Western Senate still gave the stamp of popular approval to imperial decrees, but the Eternal City had become a political backwater from which true power had long since passed. And always, just beyond the Rhine and the Danube and pressing ever harder and more frequently across them, lurked the barbarians.

Artist unknown

Much more is to be said of these in pages to come, but in short, these Nordic, Germanic peoples – among others, Alemanni, Vandals, and Goths – had migrated down out of Northern Europe, at first under pressure of their own population growth, then pushed from behind by an even more barbaric people, the Huns of the eastern steppes. The Iranian-born Alans had likewise been driven into this Central European pressure cooker. All had to decide who they could more easily push around, the ascendant Huns or declining Romans. The story of this work is the resulting struggles between foreign invaders and native-born generals, senators, and bishops, under emperors who were anything but absolute. Any man with enough soldiers behind him might declare himself emperor and even make it so, but rising to position and power was less a way to avoid violent death than to invite it.

Germanic-Roman general Stilicho with his wife Serena and his son Eucherius. Ivory diptych, c. ᴀᴅ 395 Post-Gibbon, historians have tallied over 200 reasons why the Western Empire fell, and are still counting. We will concern ourselves only peripherally with the millions of peasants, city dwellers, patricians, and plebeians who were sucked into that maelstrom, to focus more on those Romans and barbarians who aspired to mastery of the known world, most of whom never lived to see its end. Above all, there were two men – Flavius Stilicho, supreme military commander of Rome, and Alaric, King of the Goths – who had it in their power to halt the final collapse. The question, then, must be, why didn’t they? The tale of those two men, those fateful decades, and that irrevocable downfall, begins almost exactly 800 years earlier, well before even the Empire of Gibbon. Then, there was no Roman Empire at all. There were, however, barbarians. REVIEWS:

After reading this book, the fall of Rome feels less like revenge, even less like a tragedy, and more like a moment of justice. It is a multi-faceted story about empire, humanity’s basest instincts, and how the motives of the powerful often lead to the suffering of the weak. For those who love the subject of Ancient Rome, this book is a must-read. For everyone else, I would find it hard to not call this a must-read. It is a fascinating story written by a great storyteller.

In less assured hands, this could have been a turgid and thoroughly bewildering read. Thankfully, Don Hollway knows his subject inside out and neatly picks his way through the convoluted history of the late Roman Empire.... Hollway eloquently describes a treacherous, fragile world, in which the greatest empire the world has ever seen slowly collapsed under its own weight.... Overall, I very much enjoyed this excellent study of the fall of a centuries-old empire, scholarly but never dull. Thoroughly recommended. To say I thoroughly enjoyed reading this book would be an understatement. Well written, witty, and very informative, it reads like a novel, yet is non-fiction. It strikes a good balance between too academic and flippant, covering off all the relevant history at a good pace, not getting bogged down in excessive detail; I’d read several chapters in a sitting, with a single malt or coffee as company. Very recommended to persons interested in ancient Rome, or those who would like a good read. A gifted storyteller, Hollway wraps his narrative around the lives of two men prominent within the maelstrom of intrigue and war: Flavius Stilicho, the supreme military commander of Rome, and Alaric, king of the Goths.... Whether describing battles or political plots, Hollway has a knack for breathing life into history. At the Gates of Rome is a solid work of scholarship as well as a good read. Fans of Hollway’s short work already know his outstanding narrative style is matched by his impressive range. Coming on the heels of his medieval masterpiece The Last Viking, At the Gates of Rome brings Hollway’s marriage of thrilling storytelling and historical rigor to Late Antiquity. In this illuminating page-turner, Hollway walks us through the fate of one of the most significant civilizations in human history. There are works of history we return to as reference, and those we return to as inspiration. In At the Gates of Rome, Hollway has given us both. Don Hollway’s At the Gates of Rome is a masterful blending of solid scholarship and excellent storytelling that brings the Eternal City’s turbulent early history to vibrant life. Patricians and barbarians, slaves and saints, victors and vanquished leap from the pages fully formed, making the book an enthralling read from the first page to the last. The author uses the descriptions of ancient writers and more recent histories to create this account of the Western Empire’s final years. A wide range of figures are included, giving depth and detail to the narrative and revealing the vast scale of the Roman Empire and its adversaries. With so much of the writing on the Late Roman Empire dated, it is refreshing to read a work that offers a fresh interpretation of the events. ORDER TODAY:

• AMAZON • PUBLICITY CONTACTS: REPRESENTATION Scott Mendel, Managing Partner About the author

Author/historian/illustrator Don Hollway has been published in Aviation History, Excellence, History Magazine, Military Heritage, Military History, Civil War Quarterly, Muzzleloader, Porsche Panorama, Renaissance Magazine, Scientific American, Vietnam, Wild West, and World War II magazines. His first book, The Last Viking, a gripping history of King Harald Hardrada, was acclaimed by The Times of London and Michael Dirda, Pulitzer Prize-winning critic for the Washington Post. Hollway is also a classical rapier fencer and historical re-enactor. His work is also available across the internet, a number of his pages scoring extremely high in global search rankings.

More from Don Hollway:

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||